Patriotism or Nationalism? The changing meaning of the United States Flag

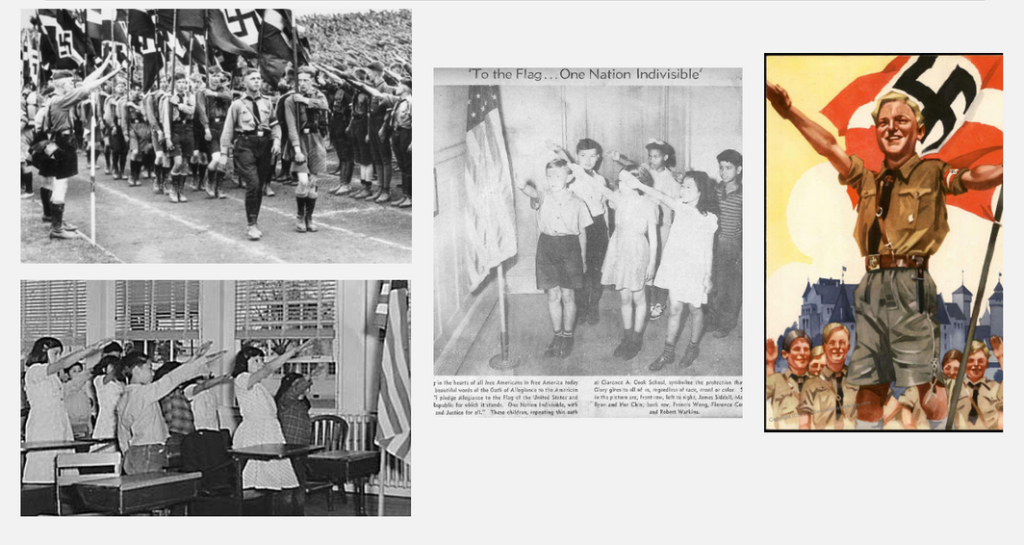

Since 2016 I’ve been thinking about the changing meaning of the United States flag from a symbol of harmony or unity to symbol of hate. It seems I’m not the only one. Research has shown that exposure to the United States flag can lead to increased nationalism and group cohesiveness. Vexillology, or the study of flags, makes note of several flags being used as symbols of hate, but for this post I’m focused only on a brief semiotic analysis of the traditional representation of the United States flag as we know it today.

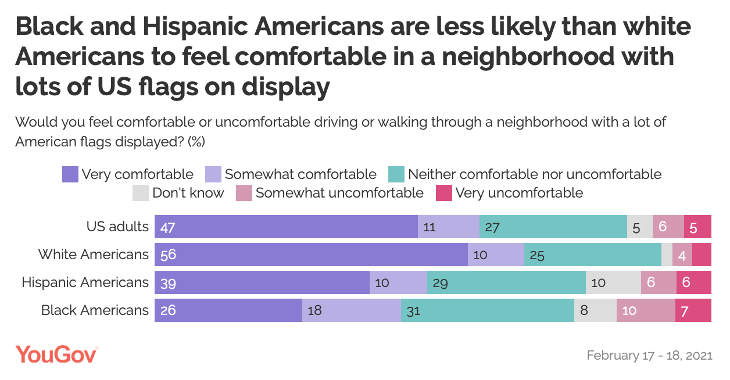

In a recent survey analyzing public opinion on the United States flag, it was found that 66% of Republicans associate the flag with their own party, yet only 34% of Democrats do. From the same survey we find that white Americans of the “Boomer” generation (55 and older) are more likely to say the flag makes them feel proud than Americans in younger generations – 86% of Boomers still love the flag, whereas only 56% of Americans aged 18 – 34 feel the any pride in the symbol of the United States.

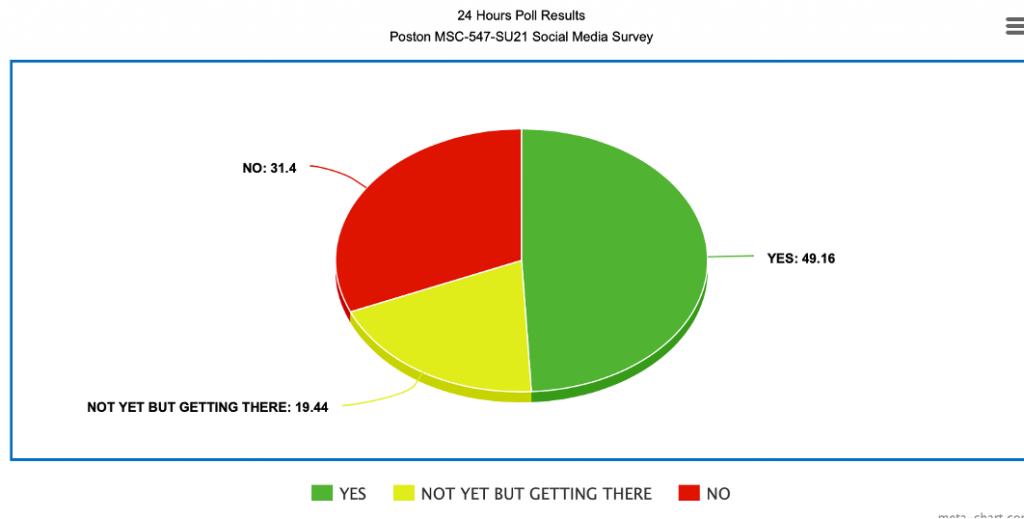

I never want to rest on my own assumptions, so I also decided to check my hypothesis by running a public, 24-hour qualitative social media poll across several social media channels, including Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Nextdoor, Instagram, and TikTok. I’d love to replicate this test in a larger setting over a longer period of time, however: the aggregate data from that poll came in as follows:

Let’s take a deeper look at the semiotics of this specific image of the United States flag as our first example

Scholars are beginning to say that the conservative “Make America Great Again” crowd has co-opted the United States flag as a symbol of their hate-fueled ideology. You can see a clear example of that in this photo in two places: in the foreground, where the anti-BLM (Black Lives Matter) protester is using it almost as a barrier to the BLM supporter’s cardboard Black Lives Matter sign, and in the background slightly to the right of the United States flag, where we see an example of one of the variations on the United States flag that has been co-opted to support various law enforcement, military, or similar groups. In this case, the black and white United States flag with the thin red line is an intertextual offshoot of the “thin blue line” flag, also an example of intertextuality. Intertextuality is the act of using one text or image to define the meaning of another text or image. The blue line in this version of the United States flag stands for police and the red line in the other version stands for fire personnel.

It’s tempting to think there is metonymy in the United States flag’s status as a symbol of hate, but the saturation point required for true metonymy to be reached isn’t quite there yet. You can say “Washington” the location as a substitute for “the U.S. government,” for example, only because of the long and public correlation between the two. Let’s look instead at some other aspects of this photo to gather context clues about the meaning of the United States flag in this instance.

| Word | Meaning |

| Intertextuality | Using one text or image to define, or shape, the meaning of another text or image |

| Metonymy | Using a concept to stand for another concept that is already associated with it somehow |

| Connotation | Serves an aesthetic function, meaning the associations or subjective meanings of a sign, image or text |

| Denotation | Serves an informational function, meaning the literal or common sense meaning of a sign, image, or text |

| Irony | Something that appears to signify one thing but its proximity to a co-present sign alerts us that it means something different (often, but not always, it means the opposite) |

| Gesture | In the context of this paper, body language |

| Binary | Opposites and pairings of symbols and concepts |

| Metaphor | A phrase that indicates unexpected similarities between unrelated things |

| Syntagmatic | Structural combinations and spatial relationships used to create meaning |

| Symbol | One of the three types of signs (the other two are icon and index), in which there is no relationship between the signifier and the signified other than what is learned |

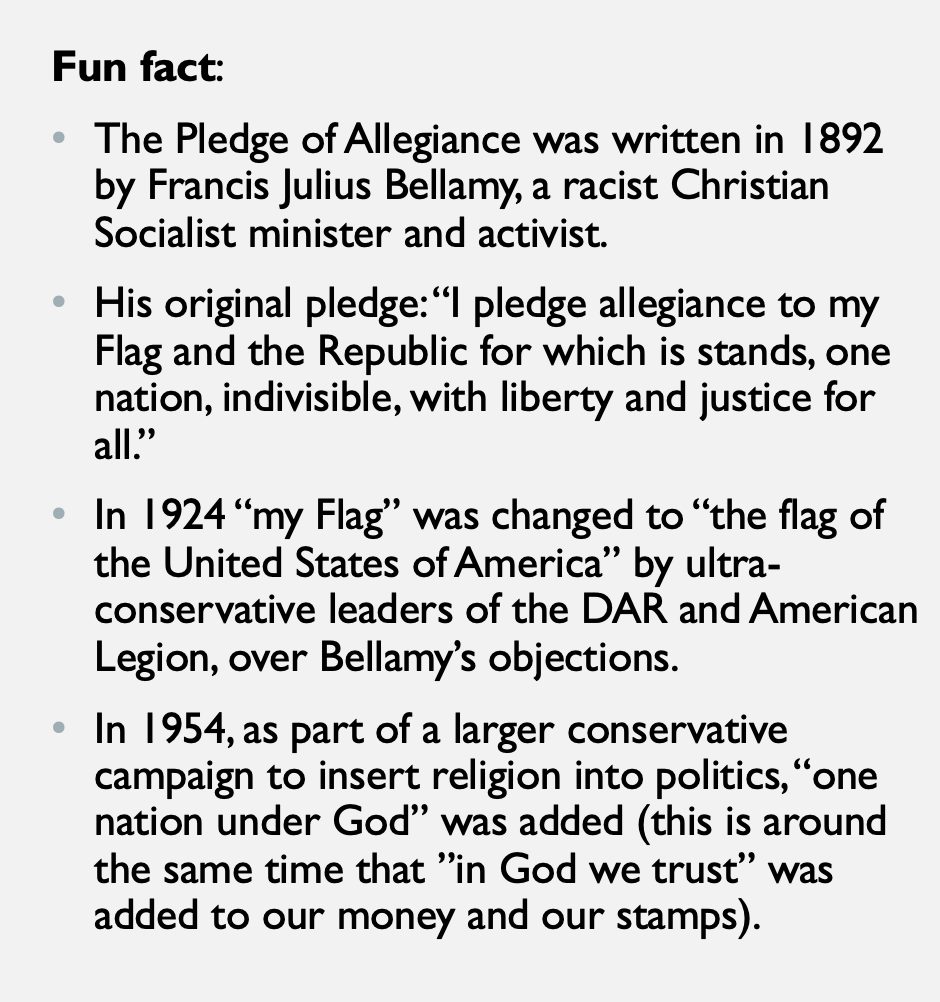

The original connotation of the United States flag is that of a symbol representing all 50 states that make up the United States (the stars) and the 13 original colonies (the stripes), with red denoting hardiness and valor, white denoting purity and innocence, and blue representing vigilance, justice, and perseverance.

In this image the man wielding the flag is angry, and, ironically, is using it to block the sign of the counter-protester (hardly a use of the flag that is pure, innocent, or just). The bald man is also angry, and it looks as if the man wielding the flag is holding him back from punching the counter-protester by placing his free hand on the bald man’s shoulder. This body language is a classic pre-fight stance. The pre-fight stance is a gesture that signifies not only anger, but a willingness to fight for a cause or belief or to fight as a remedy to a perceived slight. The fact that both angry men are not wearing masks during the first part of a global pandemic speaks to their belief systems as well, as refusing to wear a mask was an early coded gesture to indicate solidarity amongst those who were anti-BLM, anti-science, and (often, but not always) pro-Trump or pro-fascism. In fact, you might say masks (both wearing them and not wearing them) became a metaphor for each side of several binary debates: hate vs acceptance, science vs anti-intellectualism, and societal responsibility vs selfishness.

The United States flag has come to represent warring ideologies

It appears in this photo that it’s being used as a symbol of dominance and nationalism. With the photographer’s caption we know this is a pro-police protest (supported by the law enforcement insignia on the angry bald man’s shirt, symbolizing his relationship to the police) being met with a Black Lives Matter (BLM) counter protest. The body language in the photo is stoic on the part of the counter protester as he holds his sign in a strong, steady grip and stands calmly in the face of hate, looking straight ahead unflinching. The body language is simultaneously threatened and threatening on the part of the pro-police protester as he screams and gestures at the counter protester, the red face and wrinkled neck signaling a loss of control. Of the two people we can see slightly in the background of the photo, the woman looks resigned (and appears from her hat to be on the pro-police side of this debate despite facing the same direction as the counter-protester) and the man in sunglasses has a forehead that looks tense.

The cropping of the photo creates the illusion that the counter protester is acting alone, stoically standing up to hate, as if the photographer was as much attempting to create a mythology of meaningful and calm counter protest around that activity even as he was trying to capture a moment. However, there are likely other counter-protesters behind and beside him just out of frame. This choice by the photographer combined with the choice to frame the flag almost in the center of the shot is syntagmatic, using the spatial relationship of the protester and the flag to form a narrative. In this case the photographer created an illusion of solitude instead of solidarity on the part of the counter protestor and created a juxtaposition of the binary of hate and hope by placing the flag in the center relative to the protester and the counter protester.

In the far, blurry background of the photo, behind the counter protester’s head and near his hand, you can see two other United States flags in the shot, both seemingly behind the line on the police “side” of the protest. The proximity of United States flags to the police symbols of authority and power, combined with the rage seen in the bald man’s expression, denotes hate and intolerance. The presence of other pro-police signage with messages showing that the police are reacting negatively to the idea of de-funding the police and signs promoting common ideas about the military and law enforcement by thanking the police and “the troops” adds another layer of coded signage landing firmly on the side of intolerance.

The United States flag has obviously been (or is in the process of being) co-opted as a hate symbol. The question now is “how do we take back the meaning of the flag so it once again represents the country as a whole?”

*this content of this post originally appeared as part of my class for Fielding Graduate University in 2021

References

Ballard, J. (2021) What Americans think of the U.S. flag in 2021. YouGov Survey. Retrieved from https://today.yougov.com/topics/politics/articles-reports/2021/03/31/what-americans-think-american-flag-poll-data

Butz, D.A. (2009), National Symbols as Agents of Psychological and Social Change. Political Psychology, 30: 779-804

Kemmelmeier, M. and Winter, D.G. (2008), Sowing Patriotism, But Reaping Nationalism? Consequences of Exposure to the American Flag. Political Psychology, 29: 859-879.

Zink, W. (2020) From the BLM counter protest of the pro police protest in Bayside Queens, NYC on Sunday, June 14, 2020. Walt Zink Photography. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/CCpP7ZCJHoJ/

Samuel, L. R. (2020) Is the American flag a symbol of racism? Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psychology-yesterday/202007/is-the-american-flag-symbol-racism

Quito, A. and Shendruk, A. (2021) Decoding the flags and banners seen at the Capitol Hill insurrection. Quartz. Retrieved from https://qz.com/1953366/decoding-the-pro-trump-insurrectionist-flags-and-banners/

PBS (2021) The history of the American flag. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/a-capitol-fourth/history/old-glory/ Wiley-Rapoport, C. (2021) Lecture Notes. Psychology of Mediated Meaning. Fielding Graduate University